San Francisco: Researchers at the University of Washington have developed a new system called SeaGlass that helps detect cell phone surveillance by modelling a city’s cellular landscape and identifying suspicious anomalies.

Cell phones are vulnerable to attacks from rogue cellular transmitters called International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI) catchers, also known as cell-site simulators or Stingrays, surveillance devices that can precisely locate mobile phones, eavesdrop on conversations or send spam.

The Cell-site simulators work by pretending to be a legitimate cell tower that a phone would normally communicate with, and tricking the phone into sending back identifying information about its location and how it is communicating.

Described in a paper published in the journal Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, the new system was deployed during a two-month period with SeaGlass sensors installed in ride-sharing vehicles in Seattle and Milwaukee, resulting in the identification of dozens of anomalies consistent with patterns one might expect from cell-site simulators.

“Up until now the use of IMSI-catchers around the world has been shrouded in mystery, and this lack of concrete information is a barrier to informed public discussion,” said co-lead author Peter Ney.

“Having additional, independent and credible sources of information on cell-site simulators is critical to understanding how – and how responsibly – they are being used,” Ney added.

While law enforcement teams in the US have used the technology to locate people of interest and to find equipment used in the commission of crimes, cyber criminals are deploying them worldwide, especially as models become more affordable.

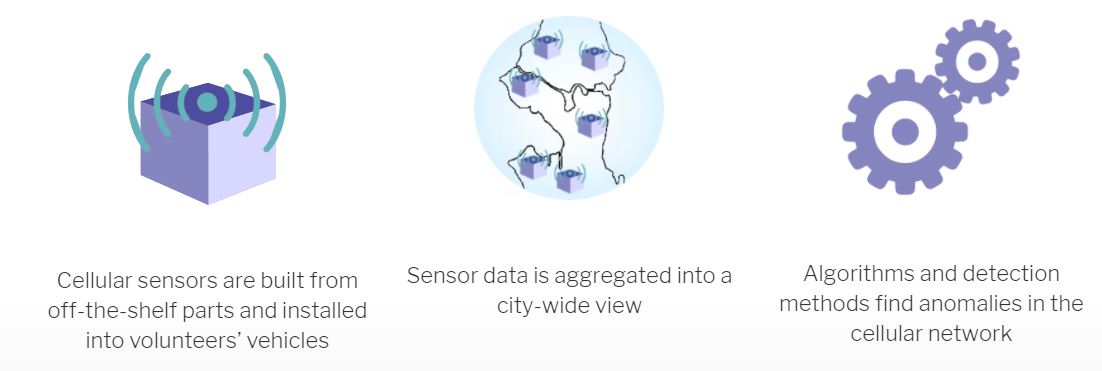

To catch these IMSI-catchers in the act, SeaGlass uses sensors built from off-the-shelf parts that can be installed in vehicles, ideally ones that drive long hours and to many parts of a city, such as ridesharing vehicles.

The sensors pick up signals broadcast from the existing cell tower network, which remain fairly constant.

Then SeaGlass aggregates that data over time to create a baseline map of “normal” cell tower behaviour.

The research team developed algorithms and other methods to detect irregularities in the cellular network that can expose the presence of a simulator.

These include a strong signal in an odd spot or at an odd frequency that has never been there before, “temporary” towers that disappear after a short time and signal configurations that are different from what a carrier would normally transmit.